By Beatriz Pimenta Klein & Yelisey Boguslavskiy

This Research is the first part of the AdvIntel LATAM Series.

Introduction

Cybercrime is an all-encompassing phenomenon, affecting both private and public domains. Cybercriminals are not only looking for financial advantages but attack geostrategic structures to provide nation-state interests. Due to the diffuse nature of threats and actors, as well as their purposes, cybercrime affects different regions in distinct ways. Latin America, as such, has a unique cybercrime threat regional profile, as the socio-economic challenges that affect the region uniquely shape the experiences of its cyber domain.

When describing the Latin American cybercrime threat landscape, one factor is especially important: the nexus between economic development, digitalization, governance, and crime. Latin American states struggle with poverty and inequality; they are still identifying their places in the global economy and supply chains; institutional-building is still a work in progress. Naturally, the institutional fragilities - the lack of cybercrime legislation, proper cyber law enforcement, technical expertise, international legal cooperation - all result in impaired cybersecurity governance. This in turn attracts cybercriminals who believe the region to be an easy target.

In this threat survey, we will examine how such fragilities as well as regional points of resilience determine the cybercrime ecosystem. Case studies of five Latin American states were selected due to their prominence and sub-continental representativeness: Brazil, Chile, Colombia, 3 representatives of South America; Panama - Central America; and Mexico - North America.

The Cause and Cost of Cybercrime

Beyond cultural, ethnical, and idiomatic similarities, another reality connects Latin American countries: dire socioeconomic inequalities. According to the GINI index, which measures income distribution, the five countries analyzed here are among the 10 most unequal states of 2018. Moreover, four other countries in this top-10 list are also Latin American. Although these nations experience robust economic growth, they provide unequal opportunities to their citizens, which naturally increases crime levels.

These socio-economic inequalities translate into traditional crime groups recently resorting to emerging digital technologies. For instance, drug cartels in Latin America profit from the lack of governmental expertise to tackle cybercrime to advance profitable transnational illicit activities, primarily money laundering. This defines the region’s threat landscape as the alliance between traditional crime, money laundering, and carding, turning financial cybercrime into the dominant trend in Latin America. As a result, cryptocurrencies-based money laundering schemes, carding, fraud, and financial malware form a complex tendency, while the banking and financial sector suffers as the main victim. As it will be demonstrated further, even nation-state APT groups, such as North Korean APTs are aiming at Latin America primarily through this prism of finance-targeting crimes.

At the same time, Latin America is a rapidly developing region accumulating wealth and economic power. Despite the above-mentioned development fragilities, many countries in the region, in the past 20 years, enjoyed economic progress that translated into the social ascension of lower-income classes. These circumstances enabled once poverty-stricken citizens to now access banking systems and sophisticated payment technologies. As a result, the expansion of financial technologies and the accumulation of wealth is also an important factor that plays a role in the rise of cybercriminal activities, especially related to financial crimes.

The annual cost of cybercrime in Latin America mounts up to $90 billion USD each year. For instance, Brazil scores the 2nd in the global ranking of largest cybercrime-related financial losses. Latin America registered an astonishing 33 cyberattacks per second in 2017. The targets of such attacks are most often banking institutions, retail, and telecommunications companies.

It is important to note that this vulnerability to cybercrime is especially critical to a developing region such as Latin America. The $90 billion USD annually lost to cybercriminals could be invested in any underprivileged area. For instance, the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) states that this money could potentially quadruplicate the scale of regional scientific research, which would immensely contribute to their regional development.

The Paradox of Interconnectivity

As reported by the World Bank, the percentage of citizens who had access to the internet in 2000 was the following:

Brazil 2,87%;

Chile 16,6%;

Colombia 2,2%;

Mexico 5,08%;

Panama 6,55%.

In 2018, the reality was radically different:

Brazil 70,43%;

Chile 82,32%;

Colombia 64,12%;

Mexico 65,77%;

Panama 57,86%.

It is clear that a quick digital social inclusion took place in the region; even though these percentages are still far from those observed in developed countries, whose levels are all above 80%. ICTs and especially Internet technologies are only beginning to entrench; consequently, the governance of the digital domain is only developing.

The Network Readiness Index (NRI) that measures the propensity of a country to explore the opportunities offered by ICT, offers the following ranks for our five countries: out of 121 countries ranking, in which the 1st country is the best performer (has the most seamless integration) and the 121th the worst, in 2019 Chile scored 42th; Mexico, 57th; Brazil, 59th; Colombia, 69th; and Panama 74th.

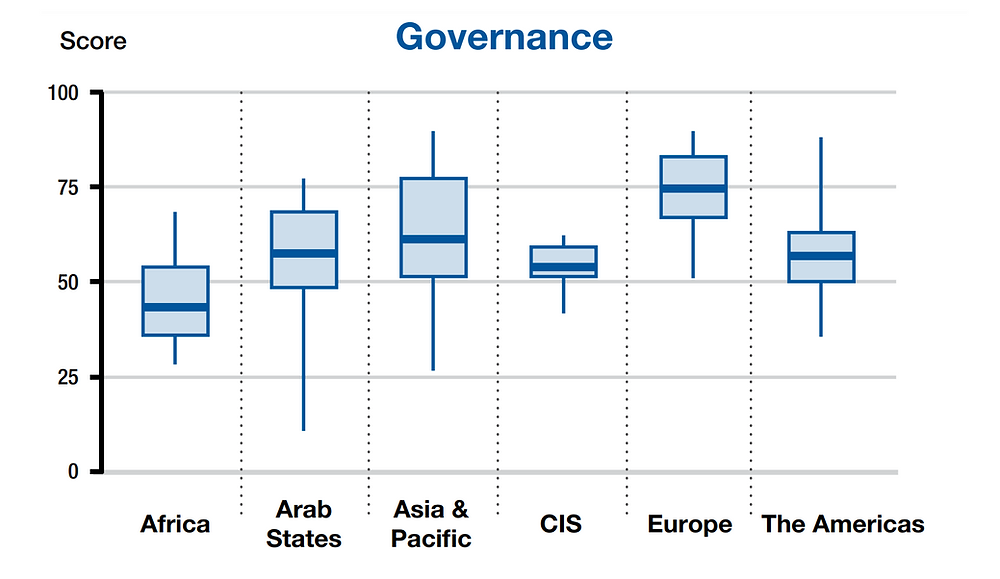

2019 NRI scores by region. In terms of governance (regulation, inclusion, and trust), the Americas’ results are only better than Africa and the Commonwealth of Independent States.

As illustrated by NRI, the digital domain is quickly evolving in the region; however, if this positive development does not follow the design of a robust governance model it may turn into an unregulated space with extremely dangerous potential: increasingly severe cybercrime.

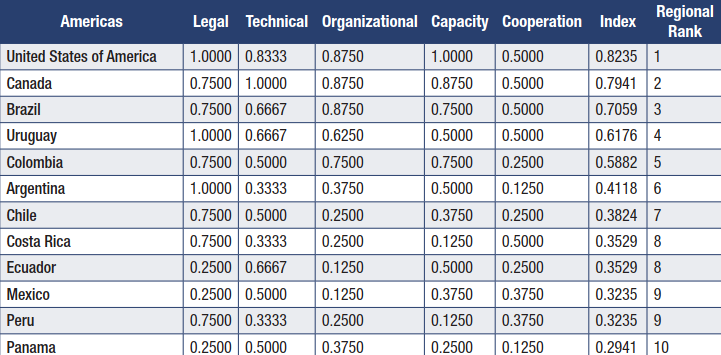

Diving in this cybersecurity aspect of ICTs, we investigate the findings of the Global Cybersecurity Index (GCI) - an initiative of the International Telecommunications Union (ITU). This index aggregates legal measures, technical measures, organizational measures, capacity building, and cooperation (international agreements, fora; public-private partnership, inter and intra-agency cooperation); providing a general framework on weaknesses and resilience aspects of national approaches to cybersecurity.

2014 Cybersecurity Index Performance of American countries. The scores range from 0.0 to 1.0; being 0.0 the worst score and 1.0 the best.

In 2018, the GCI found that only Uruguay integrally demonstrated a high level of policy commitment towards cybersecurity resilience; all other Latin American countries scored medium level, with several Central American countries scoring on the low level on the commitment scale line. Within the Americas, in 2018 Mexico scored 4th; Brazil, 6th; Colombia, 7th; Chile, 9th; and Panama, 13th. However, in a global rank, these countries stand between the 60th and 100th place (out of 121 places, which means a suboptimal performance).

The data obtained from the NRI and the GCI illustrate the positive and negative power of digital technologies. Moreover, the GCI reveals the attitude towards cybersecurity policy present across major regional states: these countries are not properly relying on international and public-private cooperation to face the challenges presented by ICTs. This highlights the lack of proper cybersecurity governance in the region, which is indispensable for a sustainable safe cyber environment for users, companies, and governments.

At the same time, the two indexes illustrate the genesis of cybercrime in the region. Cybercrime features in Latin America are specific: they are mainly related to the socio-economic vulnerability which renders criminal activity as a highly common phenomenon across the subcontinent. Given the availability of such digital technologies, traditional criminal groups decided to recur to cyber tools of a poorly regulated digital domain to obtain financial advantages.

In other words, cybercrime in Latin America is defined by the continental development fragilities - rapid digitalization with only emerging regulation and adaptation to new technologies. This vacuum of power and authority created by the novelty of expanding ICT attracts the most initiative and active actors such as traditional crime groups. As a result, threat actors find numerous loopholes in both digital and social infrastructures and are thus motivated to almost unreservedly engage in cybercrime activities.

Building Resilience and International Collaboration

Solid long-term resilience factors are also present in the region. The abovementioned figures illustrating the rapid change in regional digitalization and the damages inflicted by cybercrime on Latin American economies resulted in diverse regional responses. There are initiatives led by different international organizations. Vivid examples are the Organization of American States (OAS), the ITU, and the IDB, that foster the implementation of a cybersecurity culture in Latin America. These organizations are funding programs and sharing their reliable expertise to stimulate the creation of safe cyberspace based on good governance.

The OAS has been a prominent actor in the region, introducing best practices and implementing national cooperative measures to anticipate and respond to potential cyberattacks in the Americas. The Organization adopted the Comprehensive Inter-American Strategy to Combat Threats to Cybersecurity in 2004, and this document has been a guide throughout the years to elaborate regional plans concerning cybersecurity.

The strategy was followed by the Declaration on Strengthening Cyber-Security in the Americas, in 2012. This declaration was under the scope of the OAS’ Inter-American Committee on Terrorism, and by this time the organization was more concerned with the pervasive effects of cyber-enabled crimes. Once again this new document stressed the relevance of the creation of national complex networks of incident response teams.

A major achievement of the OAS was the signing of the Inter-American Convention on Mutual Assistance in Criminal Matters, a convention with strong potential to function as a mechanism to fight cybercrime in the continent. This specific agreement is deeply relevant because cybercrime disregards national borders, hence international cooperation based on information sharing is vital to increase States’ capabilities to investigate cybercriminal incidents.

Since 2004, the OAS has also been encouraging member states to implement the principles of the Budapest Convention on Cybercrime, and also to commit to this treaty. This Convention serves as an outline to verify the development of national policies concerning cybercrime. The five countries examined in this piece either already acceded to the Convention or are observers and candidates to the accession. This means that Latin American states are not isolated in the design of their national practices regarding cybersecurity; they are relying on international expertise and experience sharing, which is an important first step towards the implementation of good practices within national borders.

Overall, a preliminary assessment of the role played by the OAS in the continent indicates that the organization’s efforts have been decisive to the advancement of cybersecurity awareness in the Americas. The establishment of regional cybersecurity practices in the continent under the scope of this international organization, which holds authoritative legitimacy and moral authority, promotes a safe path to the evolution of national and regional policies with respect to cybersecurity.

Latin American Cybercrime Trends = Rapid Digitalization + Weak Governance

Currently, the trends in Latin American cybercrime are linked to the rapid digitalization and weak cybersecurity governance models, encompassing the link between drug cartels and hackers. The major trends are carding, cryptojacking, and BINero fraud.

Carding is especially common across Latin America, though it is not always technologically sophisticated. For instance, gas station workers illegally collect their client’s credit card info and provide the data to criminal organizations.

Cryptojacking, or a malicious crypto mining, is when the victim’s device is used to mine cryptocurrencies without the knowledge of the user.

And last but not least, the BINero Fraud is when criminals find BINs (bank ID number) incorrectly validated by online payment processors and proceed with online purchases.

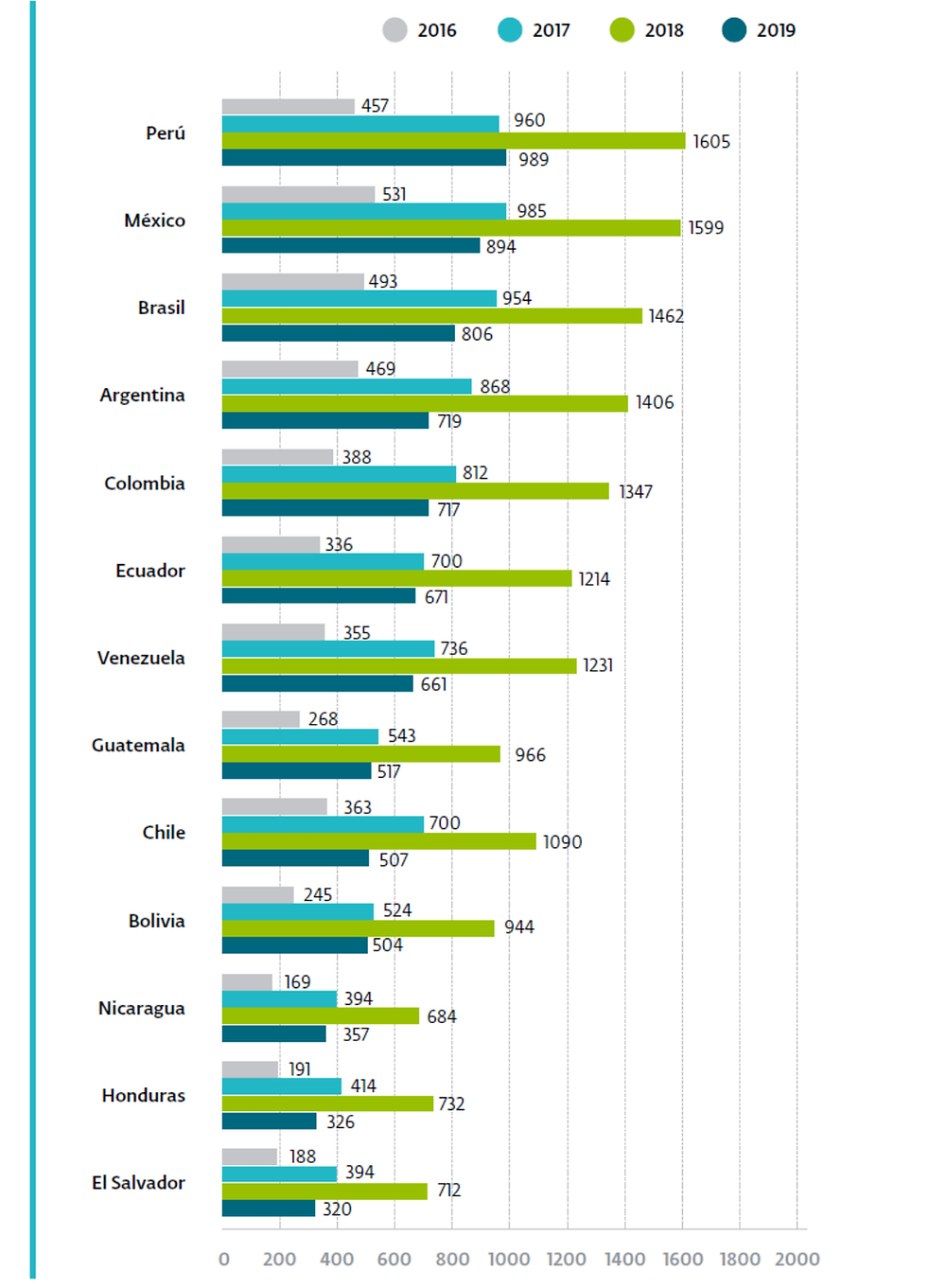

Currently, cryptocurrency-related crimes are distinctly common across the continent. Cryptocurrencies are especially compelling to criminals due to two reasons: the lack of a central banking authority and the idea of untraceable, unregulated money transfers. Usually, the legitimate exchange of cryptocurrencies is under the auspices of policies such as know-your-client (KYC) and anti-money laundering (AML); however, Latin American countries are only just developing regulations for these matters. Consequently, the region is of great interest for money-launderers and other cybercriminals dealing with cryptocurrencies. An example of this reality is that the P2P LocalBitcoins exchange point service platform registered a record increase in volume transactions between 2019 and 2020.

Amount of Cryptocurrency Miner variants in Latin American countries.

Along with cryptocurrency’s lack of regulation comes the lack of law enforcement. This allows cybercriminals to feel confident and execute their transactions through open code platforms such as WhatsApp, Facebook, and Telegram – sometimes not even hiding their identities. These platforms are accessible tools used by cartels, in which they can negotiate new fraudulent transactions directly with hackers.

Malware trends are also in line with the general vector of LATAM cybercrime - financially exploiting the emerging digitalization. In the past and current year it has been observed that 5 malware variants stand out: Catasia; Cosmic Banker; Trickbot; Phobos, and Ryuk - all five being either banking trojans or ransomware variants. Moreover, Ryuk was appointed as the last step in attacks that begin with the use of the malware Emotet, which would deliver the Trojan Trickbot - that provides the information for the employment of Ryuk.

As such, banking trojans & ransomware as well as fraud schemes are the biggest threats in the region. This data reinforces our survey’s main point that LATAM cybercriminals focus on financial crimes (be it understood under the nexus drug cartels X hackers or not) by exploiting the poor Latin American cybersecurity governance. To illustrate this point, five specific case studies are offered.

Brazil

From the early 2000s to 2014, Brazil enjoyed substantial economic growth, which resulted in the decline of poverty and social progress as well as rapid internet dissemination among the Brazilian population.

After a political and economic crisis in 2014, the country has been experiencing a strong economic recession, which deeply impacted the nation’s welfare - one of the explanatory causes of resorting to criminal activities. Yet, Brazil still figures among the 10 largest global economies. This grants the country a prominent place in what it regards as finance-related crimes, as shall be seen next.

On a global survey, Brazil stands in second place in terms of time spent in front of screens. Brazilian Internet users are very active and, consequently, vulnerable to cybercrimes. It is worth noting, though, that Brazilian authorities are committed to the creation of secure cyberspace both to the public and private sectors, through the creation of policies and institutions capable of mitigating cyber risks in different spheres.

Although the cyber governance in Brazil is not overlooked, it does not stop cybercriminals from targeting and affecting the country: the cost of cybercrime in Brazil has reached up to $20 million USD in 2018. In 2013, cybercrimes affected around 40 million Brazilian users, generating an average loss of $831 USD per victim – way above the global average, which was $298 USD that year. The most common cybercrimes in Brazil are a scam, BEC (business email compromise), and phishing, both campaigns usually originating in Brazil, in the US, and in China. As mentioned at the beginning of the report, Brazilian hackers are deeply interlinked with drug cartels and other criminal organizations.

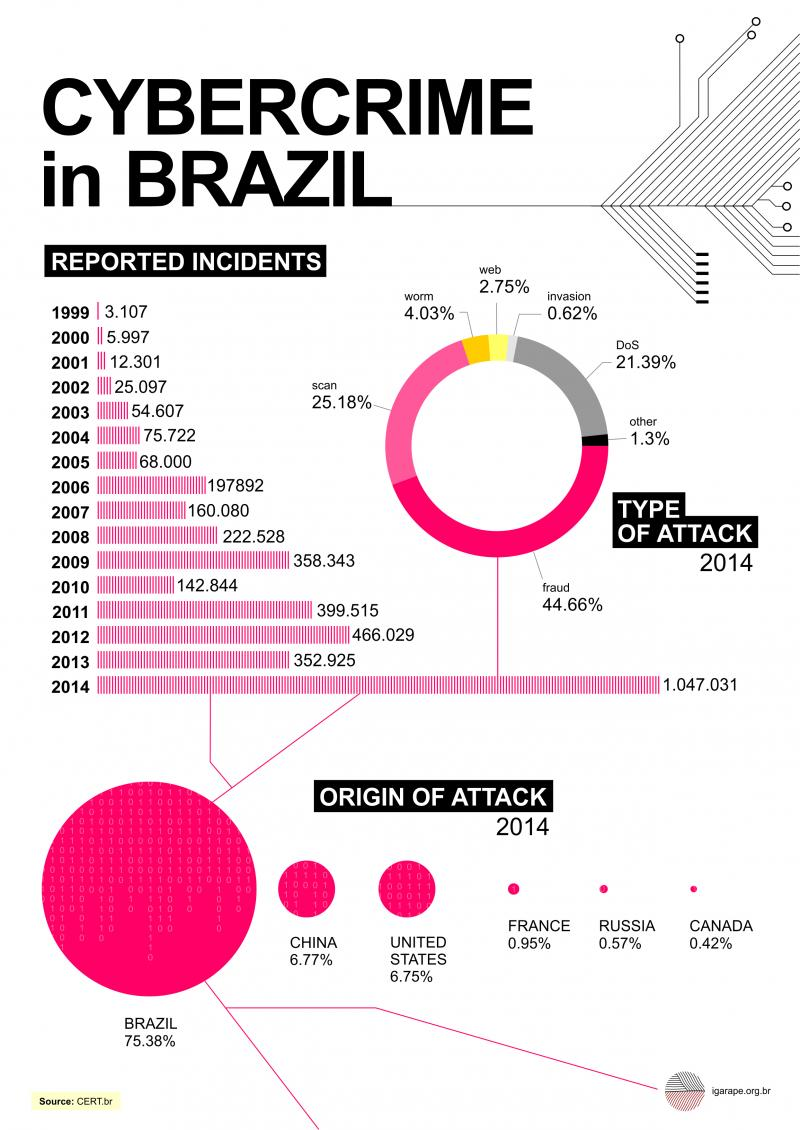

Evolution of cybercrime in Brazil with type and origin of the attack, from 1999 to 2014.

Most cyberattacks in the country originate domestically, which suggests increased cybercriminal expertise: these actors are developing original tools in Portuguese, which indicates a quick and increased professionalization of Brazilian cybercrime. This is verified by the fact that Brazil scored third place in a global rank of regional origins of malware, spam, bots, and phishing attacks.

Due to the massive number of users and consequential online transactions, Brazil is an important target for financial fraud. The country also adopted online banking technologies back in the 1990s, which makes Brazil a compelling target for banking frauds and financial crimes. These circumstances render the country highly vulnerable to financial losses, and despite Brazil’s efforts, their cyberspace is not sustainably safe for users.

Chile

Chile is one of the wealthiest countries in South America, due to, among other reasons, a commodity boom that took place in the early 2000s - an increase in revenues, propelling economic growth and financial reallocation to high-level investments. Interestingly enough, given the expressive expenditure on education and other social areas, in 2019 Chile was considered the second safest country in Latin America, only after Uruguay, according to the Global Peace Index.

Chile has launched several campaigns aiming to explore the possibilities ICT offers by developing national high-tech industries. Chilean authorities envision transforming Chile into a technological, innovation, and entrepreneurship (based on ICT) hub, a truly reference center in Latin America. For such purpose, they have launched the Startup Chile program, led by the Chilean Economic Development Agency.

Unlike its South American neighbors, the most common cybercrime in Chile is not scam or phishing, but instead malware infection. This trend is the outcome of a technically cyber-educated population that applies best practices to keep their machines and data safe. The targets, however, are similar to other Latin American countries: the financial sector, with special regard to banks. As an illustration: Banco de Chile, the second-biggest bank operating in the country, suffered a major ransomware attack in May 2018 and lost $10 million USD. The attackers performed fraudulent SWIFT (the system that standardizes international bank transactions) transfers and then employed the KillMBR wiper tool to disable the bank’s workstations and servers to boot up. Some sources point that this attack was most probably conducted by the North-Korean APT (advanced persistent threat) Lazarus group - since the group had also targeted Chilean financial institutions before, in 2017. This example illustrates how the financial cyber-enabled crimes set the tone for the Latin American threat landscape, even attracting international threat actors to profit from the region’s vulnerabilities.

This incident is just another example of Latin American banking institutions being targeted by cybercriminals, even in countries with coherent and mature legislation framework to tackle these practices. In fact, this event in Chile was pointed as being closely linked to previous attacks against Mexican banks in 2018, denoting a patterned behavior that most likely indicates the same perpetrator, most likely the North-Korean Lazarus APT group. The vulnerability portrayed by Chilean financial institutions may be explained by the exponential increase of digital banking in the past 10 years. In 2017 the country had 9 million online banking users, a number that has doubled in comparison to 2012. This online banking explosion in the country has not been accompanied by technological security measures, which allowed financial cybercrimes to be committed in the country on such a scale of what happened to the Banco de Chile in 2018.

Chilean’s high connectivity concurrently increases the socio-economic opportunities in the country - as observable through the entrepreneurship incentives such as the Startup Chile program - but it also renders the country vulnerable to cybercrime. This vulnerability is due to the fact that, if not followed by robust law enforcement development and judicial prosecution, the prolific use of ICTs in Chile can have a negative impact on the national development: financial losses, mistrust in public institutions - which all can lead to diminished foreign investments and economic capabilities, among other negative impacts.

Colombia

Colombia faces the oldest active guerrilla group in Latin America, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), with whom the country has fought through the longest civil conflict. The FARC is a Marxist-inspired guerrilla group that recurred to narco-trafficking activities as a financing method. As a result, Colombia has a dire problem with the illegal drug trade, and the country is currently responsible for approximately 70% of the cocaine global production. Colombian drug cartels are extremely active and influential, and their linkages to cybercriminals are risky: money-laundering schemes, the malicious use of cryptocurrencies, and fraudulent activities (such as carding) are all possible outcomes of the link between drug cartels and digital technologies.

Interestingly enough, though, until 2010 the Internet in Colombia was used mainly for academic purposes; from that year on it has been opened to the public. Consequently, Internet penetration has increased exponentially in the past 10 years. Despite Colombian authorities’ efforts, cybercrime accounts for around $460 USD million of financial losses a year with the average cost of cybercrime being $74 USD per victim (way below the global average). Colombia is the most affected country by phishing in Latin America, and the country is a target for financial cybercrimes.

Colombia is the third Latin American country with the most cases of cybercrime, only preceded by Brazil and Mexico. The country registers around 187 monthly law enforcement complaints related to cyber fraud. This high number of official charges (despite countless off-record cases) is illustrated by the fact that 56% of adult Internet users in Colombia are not aware of malware contagion, which denotes an urgent need for community education with respect to cyber hygiene and cyber threats in general.

The cybercrime statistics in Colombia highlight the socio-economic aspects of the digital era: with the quick digitalization, most of the population now has access to ICTs, but they are unaware of the threats posed by such technologies. The requirements to safeguard countries against cybercrime go beyond legislation and law enforcement: governments must engage in campaigns of public awareness, so the cycle of cybersecurity is complete and engages governments, companies, and users as safeguards of healthy cyberspace. And in countries that experience high levels of traditional criminal groups, the issue of cybersecurity can only be tackled through a comprehensive approach that regards the whole cycle of crime: drug cartels, financial crime, and profit-driven hackers.

Mexico

Mexico experiences a North-to-South disparity. The country sustains a developed production in the North, and lower-productivity activities related to the traditional economy in the South. Concurrently, the country is intensely involved in the global chain of production of diverse goods, so the Mexican financial flow is distinctly relevant at the regional and also global level. The relevant financial position held by the country combined with the socio-economic vulnerabilities portrayed by it render Mexico a distinctive target to cybercriminal attacks.

Mexico also confronts an alarming level of narco-trafficking activities; the Mexican War on Drugs has been ongoing since 2006. Different Mexican state agencies, supported by foreign partners such as the US and Colombia fight major drug cartels across the country and try to dismantle their activities. With the quick Internet diffusion and the consequential cyber crime possibilities, fighting criminal activities has become increasingly more complex in Mexico. To the nexus between traditional crime, drug trafficking, and money laundering has been added the cyber component, which has added a new layer of complexity to law enforcement and punishment.

Mexico is the second-largest economy in Latin America and it has a high index of Internet coverage. Yet the country is way behind other Latin American countries in what regards a general framework concerning cybersecurity. This point is astonishing since Mexico has some of the largest drug cartels in the world, who are taking enormous profit from hacking activities (the estimative is that cybercrime costs around $3 billion USD to the country), which adds pressure to Mexican cyberspace.

Some studies suggest that Mexico is also a target for attacks launched by other states. There is allegedly an increased number of attacks from APT groups against the country. Two countries have been suspected of launching these attacks: Russia aiming to undermine the US influence in Mexico and Latin America in general and North Korea aiming at illicit profits. There is also an APT group, called Careto, that since 2014 targets organizations in Latin America to obtain strategic financial and economic information. However, despite all of these diverse cyber threats, Mexico still follows the regional pattern with the most targeted sectors being banking, retail, and telecommunications sectors.

Mexico relies on three main documents concerning cybersecurity, dated from 2011 on. Yet these documents only highlight important and strategic aspects of cybersecurity to the country, but they lack specific provisions or establishment of responsible technical and specialized bodies. Consequently, Mexico’s late legislation efforts have proven to be limited. The main weakness verified in the Mexican framework concerning cybersecurity is the almost absolute lack of law enforcement as a consequence of weak/inexistent institutional apparatus, denoting inadequate management. Despite legal provisions, cybercriminals are not systematically prosecuted by Mexican authorities, which undermines the latter’s feeble attempts to fight cybercrime. This matter reinforces the image of the country as a productive soil for cybercriminal activities since there are virtually no consequences to law-breakers.

The country has a diversified threat landscape: it includes attacks from international APT groups, carding schemes, BINero fraud, online banking attacks. In 2017, the country figured 5th place in the Consumer Loss Through Worldwide Cyber Crime ranking. In the following year, 5 Mexican banks were targets of an unidentified cyberattack that resulted in a financial loss estimated at $20 million. The banks were operating with the Electronic Payments Interbanking System, a platform by the Mexican Central Bank, and the hackers managed to slow down the interbank transfer service - which enabled unauthorized transfers to take place, which was followed by withdrawals in several ATM locations. This attack points to a complex network of actors operating simultaneously, which indicates that cybercrime in Mexico is increasingly elaborated.

Panama

According to data provided by the World Bank, for the past 5 years, Panama has been one of the fastest-growing economies in the world. This economic growth results from investments in infrastructure and general traffic in the Canal; these activities allowed a sharp poverty decrease in recent years. The Canal provides Panama with a distinguishable feature: a country is a transit place where foreign companies enjoy offshore jurisdiction, converting Panama into a tax haven and a financial destination. Money laundering, then, is traditionally very common in the country, and with the emergence of digital technologies, these historic tendencies frame cybercrime in Panama. The combination of narco-trafficking, especially related to neighbor-country Colombia, and offshore jurisdiction shapes the Panamanian profile of traditional and cybercriminal activities.

Panama also lacks strong mechanisms regulating cybersecurity. The country does not possess a solid regulatory mark in the field, with outdated, insufficient laws, and feeble law enforcement mechanisms. Such a point illustrates that from 2007 to 2015, Panama had 359 investigation cases on cybercrimes; out of these 359 cases, there were only 3 convictions. So the overall environment for cybercriminals is somehow positive; the chances of getting sued and condemned for these criminal activities are extremely low, so somehow cybercrime pays off in Panama. An explanatory fact of this low rate of law enforcement is that Panama, in 2016, had only 8 computer forensics specialists to deal with all the investigations in the country, allegedly due to the lack of public resources.

The lesson learned from Panama is an urgent call for public investment in the cybersecurity area. The Panamanian profile as an offshore zone has traditionally impacted criminal activities in their territory. With the rise of digital technologies, this tendency has exponentially increased, allowing for even more pervasive money-laundering practices - most of which are linked to drug cartels in neighboring Latin American countries. As such, cybersecurity in Panama is a sensitive matter that impacts not only the country but the whole region.

Lessons Learned

Establishment multi-stakeholder initiatives such as OAS provides good examples of how beneficial an orchestrated international effort might be to nation-states. The creation of interlinked response teams and the signature of diverse agreements regarding criminal information sharing, for example, illustrate how simple measures might reduce the time taken to investigate, prosecute and condemn cybercriminals, enhancing the security of the cyber domain in the region.

Not only is international cooperation beneficial, but it also serves as a stimulus for the creation of public-private partnerships. The exchange of sensitive information between private actors and governments is highly valuable and increases the effectiveness of measures adopted by all players. Trust building, then, is crucial to enable such exchange of commercial information from private companies to state actors, to manage the risks of private rivalry.

Investments should be made aiming at the development of the educational field of technology. This could enhance Latin American countries’ capacity to adapt to new technological advancements, increasing their global position in expertise and knowledge authority. Public awareness of digital technologies is also part of this effort.

A clear institutional organization and internal division of jurisdiction in what regards cyber investigation, prosecution, and law enforcement also enable the more efficient building of domestic resilience. A combination of local-and-international approaches allows more in-depth investigative capacities, which benefit the monitoring and early-warning systems, tempering the burden of crisis response teams.

Due to the financially-centered Latin American cyber threat landscape composed of carding, scam, BEC, digital means implied for money-laundering, banking trojans - developing proper governance to tackle the financial vulnerability of the region is essential. The threat landscape is defined by the alliance between traditional crime, money laundering, and carding, requiring an investigative look of the triad. It is important to develop strategies that will regard these three pillars to make the Latin American cyberspace safer, fostering regional development.

Conclusion

Rapid design of mechanisms related to cyberspace and cyber policies is an ongoing process in Latin America. However, these mechanisms and initiatives often prove to be insufficient. The increase of cybercrime demonstrates that, despite the existent legislation concerning cybersecurity (in some countries more than others, though), these countries are lacking a robust apparatus that could constrain cybercrime in the region.

Establishing a holistic framework for cybersecurity in Latin America, and fostering regional cooperation to achieve coordinated procedures, practices, may serve as a solid response to cyber threats in the region. As pointed out, both cybersecurity and national development are closely interlinked, and the countries can engage in the effort of reinforcing their cybersecurity framework to allow the flourishing of economic and political development.

Advanced Intelligence is an elite threat prevention firm. We provide our customers with tailored support and access to the proprietary industry-leading “Andariel�? Platform to achieve unmatched visibility into botnet breaches, underground and dark web economy, and mitigate any existing or emerging threats.

Beatriz Pimenta Klein is a Threat Intelligence Analyst at AdvIntel, with a special focus on Latin America. She graduated from the Federal University of Santa Catarina (Brazil) with a Bachelor's Degree in International Relations. Beatriz is currently a Master's student in International Security Studies at the University of Trento/Scuola Superiore Sant'Anna (Italy).

Yelisey Boguslavskiy is the Head of AdvIntel's Security & Development Team