By Beatriz Pimenta Klein

This Research is the third part of the AdvIntel LATAM Series. To see other blogs within this series please visit:

Part 1: Latin America Threat Landscape: The Paradox of Interconnectivity

Part 2: Cyber Exploration: The Geostrategic Quest of APT Groups in LATAM

Part 3: Economic Growth, Digital Inclusion, & Specialized Crime: Financial Cyber Fraud in LATAM

Key Takeaways

Latin America is plagued by the constant barrage of ransomware attacks. One in every three ransomware attacks in the world targets a Latin American country. This article of AdvIntel’s LATAM series provides the tools to analyze such information. As such, this data does not come as a surprise to the attentive reader - who is, by now, well aware of the deep flaws in the cybersecurity structures of the region.

Flawed systems and remote access servers - especially relevant due to the widespread smart working modality (an outcome of the pandemic) - are the two main entry points to attackers. Attackers who manage to breach the companies’ systems can launch malware variants, encrypt files, and proceed with financial extortion. Yet, simple tactics such as phishing emails are also employed in ransomware attacks in the region. This manual type of infection has decreased in popularity, but it still represents 15% of all ransomware attack vectors in LATAM. Finally, the most common malware variant employed in LATAM is WannaCry - a malware variant that has given rise to an authentic Latin American variant, WannaHydra.

The Latin American threat landscape is shaped by the region’s socio-economic features and the evolving technological intra- and extra-regional scene. The recurrence of ransomware attacks is another facet that unveils the deep flaws in LATAM's cybersecurity infrastructure. The COVID-19 added a new layer to the already challenging scenario, with the spread of remote work and new possibilities of network breach.

Targeting specific sectors is also a new trend in the ransomware attacks phenomenon. This represents a new challenge to critical/essential industries and public agencies, since data breach may signify not only negative impact in service delivery (and potential subsequent crises) and financial losses; but these actors may also face judicial challenges due to data exposure and consequential infringement of data protection laws.

Introduction

In this last piece of the LATAM series, we focus on the incidence of ransomware attacks in the region. A ransomware attack is a type of attack that employs a malware variant to infect the victim’s computer, steal files and ultimately encrypt them, which allows the hacker to demand a financial amount in exchange for the unlocking of the system.

Latin America is plagued by the constant barrage of ransomware attacks. One in every three ransomware attacks in the world targets a Latin American country. This article of AdvIntel’s LATAM series provides the tools to analyze such information. As such, this data does not come as a surprise to the attentive reader - who is, by now, well aware of the deep flaws in the cybersecurity structures of the region.

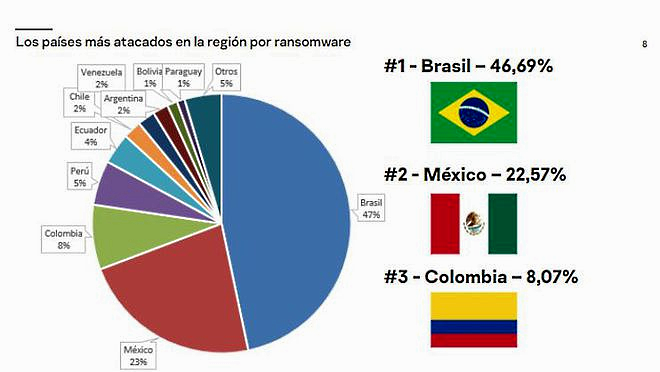

As for specific countries, it was known that Colombia was the #1 target of such attacks, yet the picture changed throughout the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic. Up to May 2020, 30% of all ransomware attacks in Latin America targeted Colombia. However, in a report from October 2020, Brazil’s statistics skyrocketed: 46,69% of the attacks targeted Brazilian companies and agencies. Apart from this ranking of victims, 40% of all Latin American companies are targeted by ransomware attacks per year, which mounts up to 5,000 ransomware attacks attempts per day between January and September 2020.

Most affected countries by ransomware attacks in Latin America, as in October 2020.

This statistical data is an illustration of the Latin American countries that lack cybersecurity governance. It denotes that not only governments, but also private companies lack proper cybersecurity plans, tools, and protocols. The vulnerabilities displayed by such companies represent a dire financial threat: the financial loss per attack is around $700,000.

Flawed systems and remote access servers - especially relevant due to the widespread smart working modality (an outcome of the pandemic) - are the two main entry points to attackers. Attackers who manage to breach the companies’ systems can launch malware variants, encrypt files, and proceed with financial extortion. Yet, simple tactics such as phishing emails are also employed in ransomware attacks in the region. This manual type of infection has decreased in popularity, but it still represents 15% of all ransomware attack vectors in LATAM. Finally, the most common malware variant employed in LATAM is WannaCry - a malware variant that has given rise to an authentic Latin American variant, WannaHydra.

This piece is structured as follows: Firstly, to demonstrate in detail the modus operandi of a ransomware attack; the variant Conti was chosen to illustrate this piece. Then, three case studies were selected to illustrate the widespread trend of ransomware attacks in LATAM, all three against private companies in essential sectors, namely energy, telecommunications, and finance. Finally, a report was selected to portray the issue of ransomware attacks in Colombia as an illustration of the consequences of ransomware attacks in a country.

Conti Ransomware: Artful Ransomware Variant

Monitoring teams have identified the ransomware variant last year in sporadic attacks, but from June 2020, a new pattern of usage is being reported: its usage has peaked. However, the mitigation of this new threat may be challenging due to the unique behavioral patterns portrayed by Conti.

The cybersecurity industry is already acquainted with the Ryuk ransomware - Conti’s predecessor. This variant was vastly deployed last year in attacks targeting different industries. Conti was initially known as Ryuk 2.0 - since Conti’s code is based on Ryuk’s, they share template similarities and both work with the TrickBot banking trojan.

Conti ransomware displays three distinctive features that make it one of the most sophisticated variants detected so far.

Support of multithreaded operations: more specifically, 32

The importance of the support for multithreaded operations is the increased speed of execution, encrypting files faster than any other ransomware variant. The high speed also grants Conti the advantage of encrypting all files before the file-locking operation is detected by any sort of antivirus.

Other ransomware variants also support multithreaded operations (such as REvil (Sodinokibi), LockBit, Rapid, Thanos, Phobos, LockerGoga, and MegaCortex), but no one supports concomitant 32 operations.

Control of the targeted victims through a command line client: the malware is capable of selecting which files to encrypt and what machines to target

Conti runs through files on the local system and those on remote SMB network shares to determine data to encrypt. These features imply that cybercriminals behind Conti are monitoring the environment of their targets since they know specifically what machines to infect. This behavior increases the level of threat posed by this ransomware variant because the cybercriminals are able to easily obtain highly sensitive and confidential data using the same entry point.

It poses a cybersecurity challenge to incident response teams to identify the point of entry into a network except if they perform a full audit of all systems. This happens because some of the machines of a network are compromised, but others are not, and the functioning of the malware undermines the capability of quick response from specialized teams.

Abuse of Windows Restart Manager

This is a relatively rare technique, barely seen in other ransomware families. Windows Restart Manager is a tool that unlocks files before performing an operational system restart. Conti uses this functionality to obtain locked files in a simple way.

Mitigation Note

The unique features portrayed by Conti ransomware create a threshold in the cyber threat landscape. The intentionality of attacks implied in the capacity to scan files before encrypting them is a problematic feature that not only but especially strategic industries should be aware of. The damage inflicted by the employment of Conti can be more devastating than previous malware variants.

As previously stated, Conti ransomware hinders the work of incident response teams. Mitigation of the damage caused may take longer than other ransomware families, so the best solution so far is to prevent incidents. There is currently no way to recover files encrypted by Conti, except for paying the financial extortion. As such, the best way to prevent such attacks is to keep secure offline backups and increase workstations’ security with the employment of security software variants.

COVID-19 & Ransomware Attacks Against the Energy Sector in Brazil

The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted different sectors in multiple ways. Social distancing measures implied a shift to working remotely. In these exceptional times, critical infrastructure sectors such as education, healthcare, energy, among others, are reporting a rise in cyber incidents from March 2020 onward, and they are especially vulnerable due to the essentiality of their work.

The energy sector has experienced a wave of cyberattacks, which were prompted by the pandemic. Four Brazilian energy companies have reported an increase in the number of cyber incidents since March 2020. The first company to be targeted was the Portuguese company EDP (Energias de Portugal), a concessionary energy provider that works in the states of São Paulo and Espírito Santo. The second was the Brazilian Energisa, which operates in 11 states in Brazil. The third was the Italian Enel, also a concessionary energy provider that works in the states of São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Goiás, and Ceará. The fourth was Light S.A., a Brazilian company that operates in the state of Rio de Janeiro. The four companies mentioned operate with power generation and transmission.

The companies reported attempted ransomware attacks, but the four of them claimed the attacks to be unsuccessful. Light S.A. was the only company that disclosed further details on the attack: the attack was allegedly initiated by REvil, demanding $15 million USD in cryptocurrency.

All companies claimed that hackers were able to access only their administrative information and could not reach the automation networks (the ones linked to the management of the energy grid). The attackers were not able to impact the automation networks, which manage the operational aspect of the industrial systems. Yet this is still a problematic security breach. Usually, security protocols of the IT network are capable of blocking further attacks to the automation network, but access to the IT network already portrays the vulnerability of this critical sector. Read more on ransomware and ISCs in our recent report available on our Andariel platform: Ransomware & Industrial Control Systems: An Unlikely Pair.

Although the attacks could not reach the ICS (industrial control systems) themselves, the administrative panels of those companies still hold sensitive information from their clients. Consequently, security breaches in this network may compromise their clients’ safety and privacy serving as a basis for third-party attacks. Moreover, the data compromise resulting from unauthorized access to the administrative panels can serve as the entry point to initiate a supply chain attack. These attacks are especially dangerous for the critical infrastructure sector as it is highly dependent on seamless supply chains.

Read more on supply chain attacks against critical infrastructure in our report: Digital "Pharmacusa" Part III: Supply-Chain Attacks for Ransomware Intrusions available at our website.

As such, in times of remote work, security should be increased at every point of their networks.

Beyond the private companies mentioned, the State-owned EPE (Energetic Research Company), which is administered by the Ministry of Mines and Energy, was also targeted by a cyberattack. It took place at the beginning of July 2020, but the nature of the attack was not disclosed. Most likely, the cybercriminals were trying to steal intellectual property concerning the strategic sector of energy in Brazil, which should put authorities on alert concerning national defense.

Mitigation Note

Especially during times of wide-scale remote work employing cybersecurity protocols is essential to safeguard the companies and their users’ best interests. The first step into a robust cybersecurity plan is to secure network infrastructure. As the experience of the above-discussed cyberattacks illustrates, investing in strong security protocols to their IT network is essential to safeguard all networks.

The required communication between devices in the energy generation and supply chain poses a vulnerability threat to the whole network. Yet risks come not only from technological vulnerability, but also from human behavior. As such, it is essential to employ measures to secure network connections. Additionally, it is also deeply relevant to train employees to identify threats and to adopt the best cyber-hygiene practices. The second step is to design authentication and policy management in order to circumvent the human factor of security.

Employing reliable third-party security software tools is a step that envisages content protection. A content security approach should also involve, for example, file-encrypting, employing blockchain (a recording of network transactions), among other appropriate measures.

Argentinian Telecom under REvil Ransomware Attack

Critical and essential sectors such as energy, water, and telecommunications are under constant threat of cybercriminal attacks. During the COVID-19 pandemic, this trend has proven to be increasing. Ransomware attacks have been reported worldwide. The delicacy of the moment requires robust efforts to prevent supply shortages.

In Argentina, Telecom - the biggest telecommunications company in the country - was targeted on July 18,2020 by a ransomware gang. The company did not disclose their intentions regarding the payment of the extortion.

Investigative Insights

The cybercriminals behind the campaign had initially demanded 109345.35 XMR (Monero coins), which is the equivalent of $7,5 million USD. If payment did not occur after 48 hours, the amount would double. This is considered to be one of Argentina’s biggest cyberattacks in history.

Phishing emails sent to the company’s employees were used as the infection vector. In total, the ransomware variant infected over 18.000 workstations of Telecom. The ransomware variant employed was REvil (also known as Sodinokibi). Responsibility for the attack was claimed by the ransomware gang through Twitter.

The group operating REvil, has also claimed another similar attack (which denotes that there is an ongoing campaign in network-based intrusions) against the French telecommunications company Orange.

To read a more in-depth report on REvil and critical infrastructure, please refer to AdvIntel’s blog.

In the attack against Orange, their clients’ information was leaked, which was not the case with Argentinian Telecom. In the Telecom case, the attack reached the internal administrative sectors of the company, and no client data was affected by the attack, nor were telephone and Internet services impacted. The only service impacted by the attack was their Call Center, which was inoperant for a few days.

Mitigation Note

The cybercriminals behind REvil use network-based intrusions to penetrate the organization's system and then spread the ransomware variant laterally across the network. As such, to prevent infection, it is essential that employees from critical sectors are trained and employ the best cyber-hygiene practices to safeguard their companies’ best interests. A simple practice is to avoid unidentified emails: users must be skilled with capabilities to identify malicious emails. This practice must be employed in every machine of the network, in order to keep the whole network of machines safe.

Companies in critical sectors must also employ third-party security solutions that will support them in emergency cases. These will include technological solutions - such as the employment of anti-virus software - but also the human capability that this type of company may offer. Knowing how to negotiate with cybercriminals behind ransomware attacks is essential to safeguard the company and their clients’ best interests, so third-party security experts, such as AdvIntel, are essential to mitigate ransomware attacks.

Maze & the Largest Data Leak in Costa Rican History

The state-owned and second-biggest bank in Costa Rica, Banco de Costa Rica (BCR), has been targeted by the cybercriminal group behind the malware Maze. The bank was targeted by a ransomware attack, followed by a major data leakage in May 2020, and there are fairly high odds that a new wave of attacks might follow.

For more in-depth investigative insights on Maze, please refer to AdvIntel’s blog post

Investigative Insights

On April 30, 2020, the Maze team published an open letter on its website stating that the group managed to breach into the BCR’s database first in August 2019 and then in February 2020. The second intrusion was supposedly a vulnerability check, and only then the group decided to steal data from the bank including 11 million credit card credentials, of which 140,000 belonged to North American citizens, and transaction histories.

Then, in April, the group threatened to leak this information, which corresponded to 2 GB of data. This is a unique ransomware attack since Maze Team decided less to simply encrypt files (which is a pattern in this sort of attack), but instead worked with the threat of leaking critical information of the bank’s clients. According to the open letter published on the webpage in April, the group claimed that they did not encrypt the files since it “was at least incorrect during the world pandemic�?.

Prior to the data leakage, the Maze team proceeded with the traditional ransomware attack modus operandi: the group demanded an unknown amount of financial extortion. Due to non-payment, the group went on and leaked the data. However, in the open letter published in April, the group alleged good intentions behind the attack: the group claims to use this attack as an alert to the lack of security to which that bank users are. The group states that the information extorted was not being sold in underground markets, nor was it being used for the profit of Maze. Data was leaked allegedly as a punishment for the BCR’s lack of security enforcement.

Current legislation in Costa Rica demands that network breaches must be reported to the authorities; yet, that was not the case of the attack suffered by the Banco de Costa Rica. The bank adamantly denies any network intrusion, even after the leakage of data. Bank representatives claim that the BCR’s cybersecurity team is unaware of any system breach, and it is undergoing an investigation to figure how the cybercriminals got the legitimate information concerning credit cards, history of transactions, and files containing the detailed specification of the bank’s network structure.

Mitigation Note

The ransomware attack suffered by the BCR is an interesting case that highlights the necessity of a robust cybersecurity plan for any company. The case above-discussed demonstrates how the bank’s digital security plan was fallible since its system was vulnerable to at least 2 breaches in 6 months. Security solutions employed did not accuse network intrusion, or, if it did, the responsible team did not level up security measures employed to the point where it could avoid a second intrusion. It is essential to employ third-party security in order to have a complete and updated plan capable of preventing and quickly mitigating any security incident the company’s network might be vulnerable to.

Third-party security companies are also skilled with best practices to deal with ransomware attacks. These specialized professionals are capable of evaluating the extension of potential damages and are capable of conducting successful negotiations with cybercriminals, avoiding data loss, and preventing any disruption of the company’s operations and image.

Conclusion

The Latin American threat landscape is shaped by the region’s socio-economic features and the evolving technological intra and extra-regional scene. The recurrence of ransomware attacks is another facet that unveils the deep flaws in LATAM's cybersecurity infrastructure. The COVID-19 added a new layer to the already challenging scenario, with the spread of remote work and new possibilities of network breach.

Targeting specific sectors is also a new trend in the ransomware attacks phenomenon. This represents a new challenge to critical/essential industries and public agencies, since data breach may signify not only negative impact in service delivery (and potential subsequent crises) and financial losses; but these actors may also face judicial challenges due to data exposure and consequential infringement of data protection laws.

Despite being especially costly to private and public companies, ransomware attacks are not markedly different from attacks from any other type of malware variant. A ransomware attack is the final stage of data breach, but the mitigation strategy must be the same as for usual malware infections: a robust cybersecurity infrastructure, solution, plan, and hygiene.

Advanced Intelligence is an elite threat prevention firm. We provide our customers with tailored support and access to the proprietary industry-leading “Andariel�? Platform to achieve unmatched visibility into botnet breaches, underground and dark web economy, and mitigate any existing or emerging threats.

Beatriz Pimenta Klein was leading the Latin America cybercrime research project at AdvIntel through the year 2020. She graduated from the Federal University of Santa Catarina, Brazil, with a Bachelor's Degree in International Relations. Beatriz is currently a Master's student in International Security Studies at the University of Trento/Scuola Superiore Sant'Anna, Italy. This series presents the findings for Ms. Pimenta Klein's findings developed through the year 2020, during the author's time in AdvIntel. The author declares that there is no conflict of interest with her current work position.