Digital "Pharmacusa" III: Supply-Chain Attacks for Ransomware Intrusions

Updated: Feb 12

In the 1st century BC, a small island of Pharmacusa (Farmakonisi) became a scene of one of the most infamous ransom extortions in history. According to Plutarch, a Roman commander Julius Caesar had to pay 50 Talents of Roman Currency to Sicilian pirates to be released. Through the next 2,000 years, rulers offered to fill rooms with gold or flotillas with silver as ransom. And even by this day, the entire cities and states can be held hostage, while governments pay millions to rescue the infrastructure. If one will need to describe the 2019 threat landscape with only a few words, "ransomware" will definitely be one of them.

The sharp rise of this menace is reshaping the entire cyber domain, filling the headlines with news about attacks against high-profile public and corporate networks. The underground community reacts by developing multidimensional structures of criminal alliances, shadow auctions, trusted groups, secretive relationships, and partnerships designed to maximize the revenue of the expanding ransomware market. These fragile unions bring together experts from all across the darkweb, who join the efforts to attack the most secure and lucrative targets.

Who are these Sicilian pirates and Pizarro conquistadors of the digital realm? Through this research series, AdvIntel offers a deep-dive into the cobweb (labyrinth) of organizational, political, and financial relationships between ransomware syndicates. By examining the stories of hacker groups and talented DarkWeb criminals, we will display how the ransomware ecosystem is becoming more complex, interconnected, and organized, while these groups themselves evolve from individual network intruders into perfectly balanced mechanisms of advanced digital crime.

Inside Supply Chain Attacks: Hidden Gateway to Some of the Most Sophisticated Ransomware Intrusions

Cybercrime: House Divided

Through most of its history, the cybercrime community witnessed a conceptual and operational dilemma between quality and quantity. One camp perceived cybercrime as an art-like challenge, in which high rewards were granted to the most inventive, creative, and patient. These hackers secretly infiltrated the most lucrative networks, remained unseen for months and stole financial and classified information from the most secure targets. The other group sacrificed sophistication in order to increase the scale, relied on automation and massive dissemination of infected samples, and concentrated on expanding the volume of their activity. The pinnacle of the first modality are Advanced Persistent Threat (APT) groups, often nation-state led elite sniper-like teams prioritizing one lucrative goal. The second approach ultimately manifests itself in the ransomware world, spray-and-pray, horizontal, decentralized.

The Russian-speaking community is particularly conservative about this divide. Ransomware was seen as an “intellectual death.” Possibly more rewarding, but definitely, way more dishonest. At the same time, crimeware developers perceived the narrow-focused specialized hackers as elitists devoted to non-functional and non-pragmatic values. However, there was one area of cybercrime in which both camps unexpectedly found a common ground and an avenue for mutual cooperation - supply-chain attacks.

One the one hand these attacks require persistence and long-term secretive presence inside the victim’s environment. On the other hand, not all environments are equally convenient. In fact, victims need to possess complex and expanded supply chains. IT, government, healthcare, oil, gas, and energy, are the best industries to target. Coincidentally, these are the sectors that provide the most lucrative opportunities for ransomware monetization, as for these industries even a minor business interruption can cause fatal consequences. This way, a supply-chain attack framework facilitated an uncommon symbiosis between APT methods and ransomware. Experienced hackers penetrate and recon the targeted industries, while digital extortionists ensure that the ultimate revenue will be received as a result.

In this investigation, AdvIntel follows the bizarre alliance and the hackers who attempt to bridge the gap between the two opposite sides of the cybercrime spectrum.

Medici of the Darkweb

The cybercrime underground has been nurturing generations of breach solutions specialists. Usually, these are talented individuals who can meticulously develop attack frameworks, steadily apply social engineering, and persistently lurk from the periphery to the center. These operations are similar to art, while efforts, time, and investments put into them will only be justified in case there is a powerful buyer who knows the real value of such work. Average sophisticated breach access costs $10,000 - $15,000 USD.

At this point, ransomware collectives act as patrons. Being on the top of the underground food-chain, they hunger for expansion and conquest of new realms. They know how resourceful a supply-chain breach can be when it comes to locking multiple systems and are eager to invest in the rising talents which can lead them to even further success. Therefore, these syndicates offer the highest rewards which can easily cover any time and expenses spent on maintaining the persistent presence. For this reason, hackers who can accomplish sophisticated third-party attacks compete in searching for the sponsor.

This can be seen with a case of a hacker operating under an alias “bc.monster”. This is an English-speaking threat actor who claims to be operating from China and who approached the Russian-speaking community in an attempt to find a right promoter. In September and October 2019, they have been actively communicating with the Russian-speaking ransomware developers and RaaS affiliate program managers. According to source intelligence, bc.monster may be currently working as an affiliate of at least two RaaS groups.

Simultaneously with joining ransomware teams, bc.monster was participating in underground auctions in an attempt to prove their value for the community. As they tried to attract attention, bc.monster even volunteered to share evidence of the breaches, which is very uncommon for network intruders (sharing evidence with the wrong audience can lead to the loss of access). For the same reason, they keep their prices relatively low - often between $1,000 and $5,000 USD.

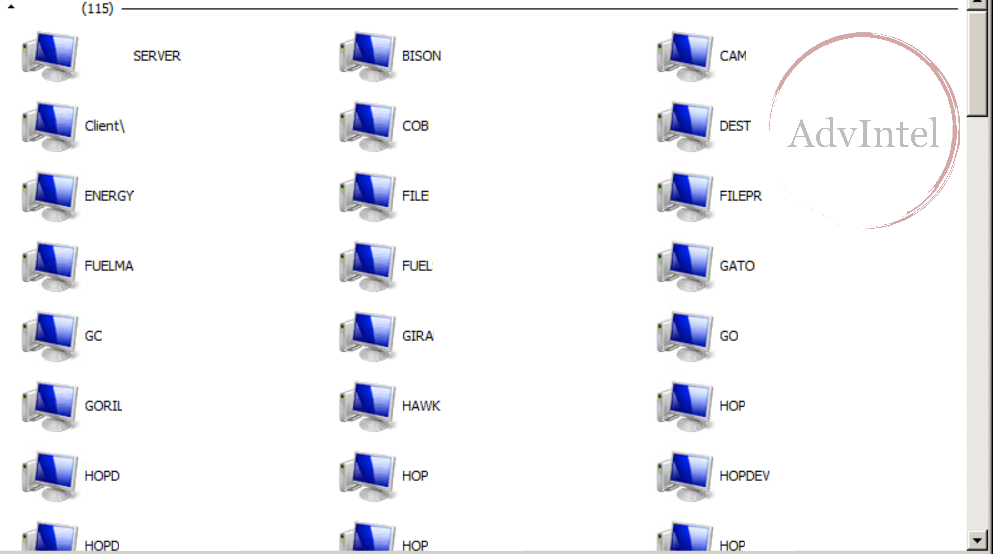

In September 2019, they were able to utilize RDP compromise in order to breach into a US energy company. While discussing the breach via private messengers, bc.monster indicated that they enable the buyer to impact customers and vendors of the victim as well, emphasizing the third-party attack vector. They have offered evidence of multiple workstations within the breached network which would allow entering other entities.

A similar case was observed in July 2019, when a Russian-speaking hacker “x444x0” a participant of the BURAN RaaS team obtained access to a segment of a telecommunication network and began navigating through it, escalating their privileges. This way they have received credentials for the domain controller of an Australian telecommunication provider offering internet coverage for business and corporate clients with access to over 9000 personal computers within the network. As a result, X444x0 had remote access to thousands of devices within the telecommunication customer chain.

According to AdvIntel sensitive source intelligence, x444x0 aimed to sell this access to BURAN or other larger groups that can successfully lock all the systems to which the hacker had remote access for $5,000 USD.

Ultimate Integration

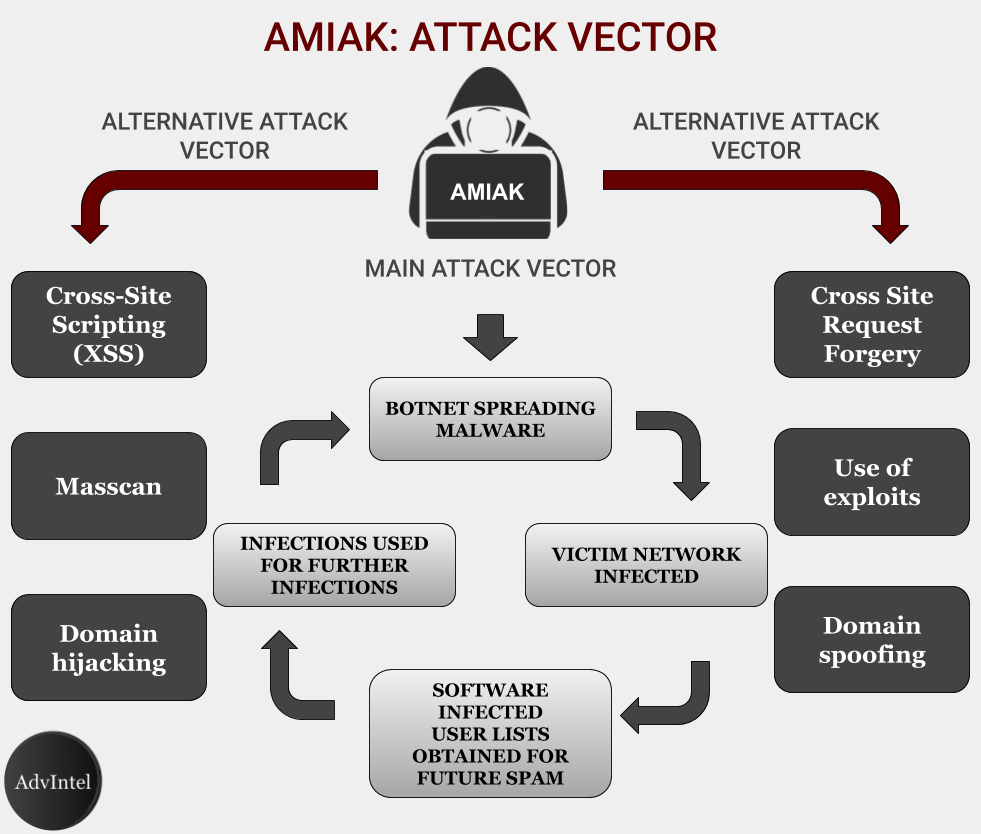

Collaboration with external affiliates is often helpful, but not every ransomware group relies on this support. Some prefer to accomplish the supply-chain attacks all by themselves. “amiak” a Russian-speaking ransomware collective formed in June 2015 which specializes in targeting corporations, refuses to rely on others, even though third-party attacks and other offensive operations requiring persistency are their ultimate specialization.

This is partly related to the fact that “amiak” themselves - the individual behind the group - built his cybercrime career as a network specialist. According to AdvIntel’s sensitive source intelligence, amiak joined the cybercrime community in 2010, when they became a member of a now-defunct criminal group linked to CarderPlant, leading an underground forum with the same name and being responsible for massive breaches, including the NASDAQ breach of 2013. After the group’s activities were terminated by international law enforcement, amiak decided to organize their own team currently consisting of at least 5 people. The collective currently has web inject manager, botnet manager, exploit kit developer, and, of course, ransomware specialist. As such, amiak can perform different attacks in order to upload their ransomware.

The group uses a wide range of infection tactics:

SQL injection

Cross-Site Scripting (XSS)

Сross Site Request Forgery (XSRF)

Attack on Git repositories

Use of exploits, specifically for the following vulnerabilities:

CVE-2015-4603

CVE-2015-6659

Masscan vulnerable port attacks

Content Management System (CMS) attacks

Domain hijacking

Domain spoofing

Credential stealing

Cloud service infections

Masscan vulnerable port attacks

Content Management System (CMS) attacks

Domain hijacking

Domain spoofing

Credential stealing

Cloud service infections

Their first tracked victim was a national university located in Mexico, which is one of the largest universities in the Americas. amiak hijacked the university’s main domain and sold it for $300 USD in February 2016. Other notable targets included:

A global communication equipment provider

A major Philippine financial institution

Police department

European financial institution

Crypto-currency exchange

The most interesting attack occurred in July 2019, when the group offered access to a Canadian point-of-sale (POS) software provider. According to amiak, the main value of this access was the ability to spread malware through manipulating the driver upload. The group presented a list of potential victims who are all clients of the main target using its software. The list contained over 185 names and included major retail chains in the US and Canada.

Essentially, amiak not only performed a supply-chain attack but incorporated it into its ransomware dissemination model. First, by using the botnet, amiak obtains the initial access. By using their network penetration skills, developed during the time in the CarderPlanet community, the hackers secure the initial access, investigate the network, and, most importantly, reach the supply chain itself. Most often, they target software companies and attempt to infect the software drivers which will be then distributed to customers. Next, amiak performs the attack and locks the system with ransomware, while using some of the machines unimpacted to enhance the capabilities of the botnet and infect new victims. This way they close the cycle.

Conclusion

A supply-chain cyber-attack unites the seemingly ununitable - massive scale-based automated dissemination of ransomware and selectively targeted attacks requiring the persistent presence and protracted recognizance.

Such a combination turns an already lethal attack methodology into something far-more perilous - a foundation for a newer ecosystem. The promises of high rewards and fame offered by this methodology cause traditional cybercrime communities to shift their behavior. Previously independent individual network intruders like x444x0 seek patronage from large and wealthy ransomware collectives. Some, like the Chinese bc.monster, even perform digital migration, attempting to find a champion among the Russian-speaking cybercrime. At the same time, the affiliates of elite ransomware syndicates are keeping a close eye on the community and are eager to invite a highly-skilled professional for hire, to initiate an APT-style joint operation against a defense contractor or an investment fund.

This mutual cooperation will only expand in the future, making supply-chain attacks even more prolific, and, therefore, making ransomware even more deadly.

AdvIntel has preemptively notified US law enforcement about all the incidents described in this research.