By Beatriz Pimenta Klein

This Research is the first part of the AdvIntel LATAM Series. To see other blogs within this series please visit:

Part 1: Latin America Threat Landscape: The Paradox of Interconnectivity

Part 2: Cyber Exploration: The Geostrategic Quest of APT Groups in LATAM

Key Takeaways:

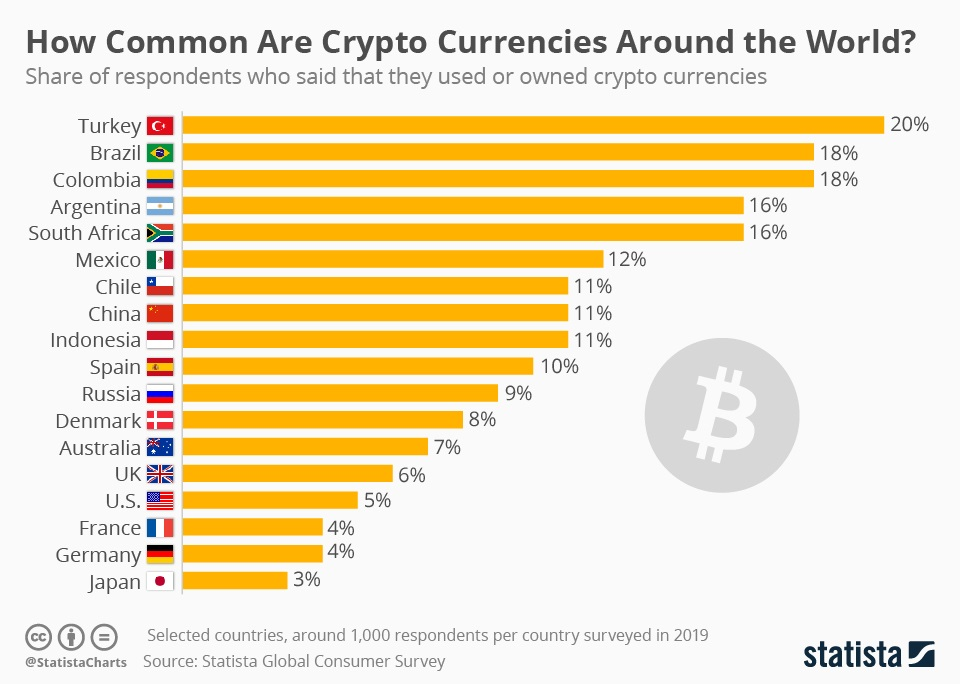

Due to political and subsequent economic instability experienced in Latin American countries, which tend to devalue currencies, cryptocurrencies are an easy alternative to conserve one’s personal wealth. This financial option has proven to be the preferable choice of many Latin Americans due to the safety and facility to engage in transactions, especially when sending money to family and friends abroad. Indeed, in a global poll, LATAM is the region with the highest number of cryptocurrency users.

With the recent possibility to open a bank account online, a trend emerges: identity theft and consequential fraudulent new bank accounts. Again, Brazil holds 1st place in the Latin American ranking of identity theft crimes: yearly, the country faces a loss of $60 billion Brazilian reais (approximately $11,3 billion). Fraudulent bank accounts allow the cybercriminal to sign loan contracts and contract debts in another person’s name. These activities do not only affect the victim and the bank but also negatively impact the whole dynamic of DFS, implying further regulations that might hinder financial inclusion and positive user experiences.

Furthermore, malicious software variants are spread throughout Latina America. Previously these malware variants did not originate in the region; however, new communities of Spanish and Portuguese-speaking hackers changed this reality.

Globally, the financial sector is the second most affected sector by cybercrime - behind only retail. This reality is not different in LATAM. Banks and other financial institutions face challenges that regard fraud, be it due to identity theft (as discussed above) or trojan and backdoor mechanisms. The Emotet botnet (targeting mostly banks) presence in the region represents 45% of the global employment of the tool. In general, in 2019, LATAM suffered 85 billion attack attempts in regards to malware variants and botnet activity, the most affected country is Brazil with 24 billion cyberattacks in a year.

Introduction

The causes for financial cybercrime in LATAM have been discussed in a previous AdvIntel report, in the current report, a few case studies were selected to illustrate the diversity of the Latin American financial cyberthreat landscape.

Along with and driven by the boom of online shopping and balkanization, Latin America also experiences the emergence of different types of frauds and further financial cybercrimes. Previously only portrayed as targeted victims, Latin American countries are starting to witness the creation of hacker groups capable of deploying cyber attacks in the region and elsewhere. Latin American cybercriminals have been developing their own codes in Spanish and Portuguese languages and launching national and regional attacks, and now they have grown to a point that they started a process of cyber-internationalization.

This report is structured as follows: there will be a brief discussion followed by case studies for three subsections, namely the case of cryptocurrencies, financial crimes targeting users, and crimes targeting financial institutions.

Cryptocurrency-Related Cybercrimes

With the rising popularity of cryptocurrencies, banking trojan families are no longer targeting only formal banking institutions and their users. The design of banking trojan variants increasingly includes functions related to cryptocurrency wallets. In Latin America, where these currencies are progressively popular, fraud schemes that encompass cryptocurrencies are a trend.

Due to political and subsequent economic instability experienced in Latin American countries, which tend to devalue currencies, cryptocurrencies are an easy alternative to conserve one’s personal wealth. This financial option has proven to be the preferable choice of many Latin Americans due to the safety and facility to engage in transactions, especially when sending money to family and friends abroad. Indeed, in a global poll, LATAM is the region with the highest number of cryptocurrency users.

5 Latin American countries stand in the top 10 countries with the highest number of crypto users.

Despite the positive aspects of cryptocurrency, its vast use does not come unaccompanied by negative consequences. Due to blockchain technology, which allows for the almost absolute untraceability of transactions, these currencies are being used for money laundering purposes. According to “The Dark Side of America Latina” report, this malicious use takes place in three ways:

Through a cryptocurrency tumbler, which mixes legitimate crypto with compromised ones (dark web crypto, for instance);

Benefiting from the lack of or weak national regulations when it comes to know-your-customer (KYC) and anti-money laundering (AML) policies;

Resorting to illegal peer-to-peer (P2P) exchanges to launder illicit cryptocurrencies.

As a result, 97% of all washed cryptocurrencies end up in LATAM, due to the loose regulations displayed by these countries. What can be inferred from these pictures is that Latin America offers great opportunities for cryptocurrency-related crimes.

Yet, as in any space where financial transactions occur, cryptocurrency wallets are targets for cybercriminals. Users are not spared from cybercriminal activities, and we have been witnessing the creation of malicious software variants targeting users. A few case studies are offered below to illustrate the current situation crypto users are vulnerable to.

Case Studies

Metamorfo, the Banking Trojan with Cryptocurrency Theft Mechanisms

Metamorfo, also called Casbaneiro, was first spotted in May 2018 in Brazil, and since then, it has been quickly spreading through Latin America. Mexico is their second most-targeted country; yet, infections have also been recorded in the US, Chile, Argentina, Peru, Ecuador, and Spain. Metamorfo targets more than 20 online banks in Brazil and around 7 in Mexico. The malware variant is believed to be of Latin American origin, among other reasons, due to its capability to scan, detect, and target specific Latin American banking applications available at the infected device.

Infection vectors employed by Metamorfo’s campaigns are mainly phishing emails with attached malicious files. Yet it can also be delivered through fake update messages from WhatsApp, Spotify, and Onedrive that mimic official communication, and that will induce the user to download the malicious file that contains the malware variant.

Once Metamorfo infects the machine, its backdoor capabilities, which are very common among Latin American banking trojan families, include: taking screenshots (that are sent to the C&C server), keylogging (keystrokes recording), simulating mouse and keyboard actions, and restricting access to specific websites. Besides that, Metamorfo can also download and execute supplementary executable files, additional malware variants such as cryptocurrency miners, ransomware variants, and further malicious software families. It is interesting to note that Metamorfo uses Youtube to host its C&C servers’ domains. The YouTube accounts used are related to cooking recipes and football.

Beyond the above-mentioned capabilities, Metamorfo also collects the user’s operational system version, user name, device name, and all installed anti-virus solutions. Finally, Metamorfo verifies which banking applications the machine holds, especially security ones, such as Diebold Warsaw, and Trusteer.

The banking trojan variant constantly monitors the victim’s activity to collect online banking credentials; it then displays a fake version of the banking website that mimics the official one, so the user inserts their credentials into this fake mechanism.

Their technique regarding cryptocurrency theft is increasingly common in Latin American banking trojan families. The user records their receivers’ addresses in their cryptocurrency wallet. When the user wants to perform a transaction (transfer or deposit), they will usually copy and paste the intended address into the transaction page. Metamorfo intervenes in this dynamic by substituting the copied address (with the intended receiver’s address) with another criminal address.

Mitigation Note

The mitigation of the banking trojan issue is done through a combined strategy between technological and behavioral measures. In terms of behavior, users must be engaged with cybersecurity best practices, which include knowledge about how to identify phishing emails and how to act in the case. Users must also be skilled with basic knowledge to identify fake communications of official applications and services, in order not to download fake files that mimic authentic programs.

In technological terms, the user must run potent and updated security solutions. These tools will help the user to identify and remove potential threats before infection; and in the case of infection, it will support the user with a fast incident response action plan.

VictoryGate, Cryptojacking Botnet

Is no surprise that cybercriminals are developing malware variants that are cryptocurrency-related. One of these variants is the malware type known as cryptojacking, which is the undercovered and malicious use of a victim’s device to mine cryptocurrencies. VictoryGate is exactly this type of malware.

VictoryGate was first spotted in May 2019, and it targets mainly Latin American users. More specifically, it targets Peru, where 90% of infected machines are located. The cryptojacking nature of VictoryGate means that what cybercriminals are looking for is the computational power of their victims, and not money or other types of information. VictoryGate works, then, as a botnet - a network of machines interconnected to a server and that will mine cryptocurrencies without the consent of the machines’ owners. There are no specific victims: there were reported victims both in public and private sectors, which also included financial institutions.

In this specific case, the malware variant is specialized in the Monero (XRM) cryptocurrency. This specific cryptocurrency is increasingly popular among cybercriminals, due to their focus on privacy. This privacy feature and the consequential use of the cryptocurrency for illicit activities made exchange platforms exclude Monero from their accepted cryptocurrencies. The second feature of Monero that also contributes to their popularity among hackers is their miner algorithm being resistant to ASIC miners, which allows domestic mining (without the use of a specific miner machine).

Over 35.000 machines are believed to be infected by VictoryGate from 2019 on. By February and March 2020, 2.000 infected machines connected to the malware server daily, mining more than 80 XMR (approximately $6.000).

Their main infection vectors are infected USB drives. When these USB drives are connected to the victim’s machine, it installs the malware VictoryGate. The malware code contains an Autolt agent that constantly scans new USB units, which allows the malware variant to spread to additional machines. The botmaster is also capable of updating the functionalities of VictoryGate, which increases the level of threat posed by this malware variant since their functionalities can evolve into any sort of malicious tool.

Mitigation Note

Having a robust cybersecurity solution is the first step to mitigate the threat of cryptojacking malware variants. These tools are constantly scanning the machine for unusual and suspicious usage of the CPU, which can rapidly detect the presence of a cryptojacking malware such as VictoryGate - a malware variant that can use up to 90% of the CPU capacity of the machine.

Since their main infection vectors are USB drives, critical machines must be spared from the use of such devices, which can be easily infected. Running the antivirus solution on the drive before opening any file contained in it is also an important step to prevent infection.

Financial Crimes Targeting Banking

Besides the specific cases of cryptocurrency users and crimes targeting their wallets, multiple financial cybercrimes are affecting online banking users. Only in the first semester of 2020, financial data theft rose 43% in Brazil, for instance. This type of statistic indicates the undermining effect such crimes have on the level of trust of users in digital financial services (DFS). In a region with comparatively low levels of financial inclusion, low trust in DFS can have relevant impacts on the economic growth and international integration of such countries.

With the recent possibility to open a bank account online, a trend emerges: identity theft and consequential fraudulent new bank accounts. Again, Brazil holds 1st place in the Latin American ranking of identity theft crimes: yearly, the country faces a loss of $60 billion Brazilian reais (approximately $11,3 billion). Fraudulent bank accounts allow the cybercriminal to sign loan contracts and contract debts in another person’s name. These activities do not only affect the victim and the bank but also negatively impact the whole dynamic of DFS, implying further regulations that might hinder financial inclusion and positive user experiences.

Furthermore, malicious software variants are spread throughout Latina America. Previously these malware variants were not originated in the region; however, new communities of Spanish and Portuguese-speaking hackers changed this reality.

Case studies

Three-in-One: Mekotio, the Banking Trojan with Multiple Functions

New hacker groups increasingly flourish in Latin America, creating their own communities of Spanish/Portuguese-speaking cybercriminals. Within these groups, banking trojans families are fairly common across the region. These malware variants are usually looking for private financial information from internet banking users. Yet a new form of banking trojan emerges: variants that are looking for cryptocurrency. Mekotio is a fairly new malware variant, and it is one example of this new type of banking trojan.

First spotted in March 2018, the Mekotio campaign usually targets South American countries. Over 50% of their attacks target Chile, around 30% target Brazil, 12% target Colombia; Peru, Argentina, Ecuador, and Bolivia are minor targets. More recently, though, Mexico has also become a target for Mekotio campaigns. Their targets are 51 financial institutions distributed across the above-mentioned countries.

Their infection vectors are phishing emails with malicious links. These emails mimic official governmental agencies, and the message is usually about taxes and receipts. When the user clicks on the malicious link, the webpage requests the user to download a .zip file, and the malware variant then infects the machines.

Mekotio has three major functions: stealing banking information, cryptocurrencies, and passwords stored in a web browser. Concerning banking information, Mekotio monitors accessed webpages, and when the user accesses their banking page, the malware variant displays a fake banking website that mimics the official one. Upon insertion of personal credentials, Mekotio sends this information to their server.

In order to steal stored passwords, the malware variant is designed to be executed as a user application. The encryption mechanisms employed by password managers are designed to allow decryption only by the same user of the operating system that first encrypted it. As such, Mekotio can decrypt such information. These passwords might be linked to banking information or they can be related to other personal accounts, such as email, social media, storage database, etc. Consequently, this is a highly threatening feature.

To conduct a cryptocurrency transaction, the user must have the receiver’s address in their cryptocurrency wallet. So these addresses are usually copied and pasted to the transfer/deposit area. When the user’s machine is infected by Mekotio, the address pasted to the transfer/deposit area will not correspond to the intended copied address. However, the user will usually not note such a difference and will carry on with the operation; consequently, the cybercriminal will receive the cryptocurrencies, instead of the intended receiver.

If the cybercriminals behind Mekotio are interested in cryptocurrencies, it means that these actors are targeting specific individual users, not any person. It means that these cybercriminals somehow monitor cryptocurrency users to target them specifically.

Mitigation Note

Since their infection vector is mainly phishing emails, cybersecurity best practices must be employed to avoid infection. These measures include not opening suspicious/unknown emails, and especially not clicking on any link contained in these emails. The same is valid for files contained in these unidentified emails.

Systematically running anti-virus solutions is also of great importance, so even if the machines get infected, the user can still be safe.

Concerning cryptocurrency theft, it is essential to always check the cryptocurrency wallet and to verify if the address in the transaction area is indeed the intended receiver of the cryptocurrency deposit/transfer.

WannaHydra, 3-in-1 Brazilian Banking Trojan

The WannaCry ransomware global campaign in 2017 seems to have left its legacy. After its massive attack three years ago, WannaLocker, a mobile adaptation of WannaCry emerged. Yet, this was not the final stage of the evolution of this malware family. WannaHydra is a new malware variant that draws on the WannaCry-inspired WannaLocker, but with added malicious functions.

So far, WannaHydra has only been identified in Brazil, but it definitely has the potential to spread elsewhere and cause great damage as its predecessors did.

The newly designed WannaHydra is a malware variant that affects iOS and Android users in a campaign that targets exclusively Brazilian online banking clients. Three banks have been identified as targets of the malware variant: Itaú, Santander, and Banco do Brasil. The most important and distinctive feature of WannaHydra is the fact that it combines three types of attack in just one malware variant: WannaHydra displays features, at the same time, of a remote-access-Trojan (RAT) malware, spyware, and ransomware. All of these characteristics combined in one solid banking Trojan. In fact, WannaHydra has the same User Interface as WannaCry in its ransomware module, but, as above-cited, it has more capabilities than its predecessor.

It is not confirmed how the malware variant infects mobile phones. Yet, as WannaHydra mimics official online banking apps, the most probable infection vector is through download in unofficial app stores or malicious links. Then, WannaHydra’s modus operandi is the one that follows: once the app has been installed on the victim’s phone, the malware variant executes its banking Trojan function and delivers a warning to the victim, alleging a problem in the user’s bank account. It then portrays an interface that mimics the official bank’s app and requires some login information. This information might include the user’s social security number, credit/debit card number, and password - and this sort of information is not usually required by authentic banking apps. When the user provides this information, the cybercriminals behind WannaHydra get access to the victim’s bank account.

After this first data breach, WannaHydra activates additional functions. The first one activated is the spyware function, and the malware variant carries on collecting all sorts of personal information from the victim. This information may include GPS location, microphone recording, storage media, call logging, SMS, hardware information, among others. This sort of data is used for ransomware attacks: WannaHydra utilizes a Portuguese version of WannaLocker, which, additionally to all the above-cited breached information, also has the capability to activate the smartphone’s camera and take pictures. The device is then encrypted and a ransomware attack takes place.

Due to the novelty of the malware variant, it has not been disclosed how much money is demanded in ransom payment. Another still unknown information is the number of victims affected by WannaHydra.

Mitigation Note

Recent research in Brazil has found that 30% of Brazilian users cannot identify fake banking app interfaces that mimic official ones, mostly assuming it to be authentic. This is a piece of alarming information that illustrates the potential damage these apps can cause.

To mitigate such a problem, a few actions can be taken. The first and most basic one is to never click on suspect/unknown links - and this step can mitigate diverse cyber threats. It is important also to only download apps (especially banking ones) via official stores, which are constantly scanned for malicious applications. For Android users, it is also possible to activate Google Play Protect, a security function of the Play Store that scans all installed apps for potential malicious hidden software variants. Overall, for all users, it is absolutely mandatory to employ security software solutions such as antivirus and firewalls that will constantly scan the phone and will keep the device, the user, and its private data safe from cybercriminals.

BRata, the New Real-time Surveillance Brazilian Trojan

BRata, or Brazilian Android Rat (remote access tool), a new malware family that already counts with more than 20 variants.

The malware was first detected in January 2019 and its distinguishable feature is the ability to remote control the victim’s mobile phone in real-time. The malware family mimics a WhatsApp update version, WhatsApp v2.0, and it has been downloaded over 10,000 times from Google Play Store in one year. As the name suggests, the malware family’s creators are Brazilian. They target Brazilian Android users - users of Android 5.0 or more recent operational versions. The fake app has been deleted from the Play Store, and its developer has been banned from the platform; however, the malware variants may still be employed, since they also use other infection spread vectors such as push notifications on compromised webpages, messages delivered via WhatsApp or SMS, and sponsored links in Google searches.

BRata is a financial malware that targets users, not the banks themselves, and it has great potential to be employed against other industries. The malware is designed to steal banking information from mobile devices, rather than target specific bank systems.

Once the victim’s mobile phone is infected, the malware surveils the device in real-time. BRata allows the controller to read the victim’s emails and messages, to control phone calls, to see browsing history, to access media, and it also can allegedly exploit the device’s camera and microphone. All of these functionalities are initiated through keylogging, which is a malicious record of keystrokes used to steal the information inserted by the user on the device. However, the malware also resorts to "living off the land" tactics exploiting in-built tools to surveil the victim’s phone: it explores Android’s Accessibility Service, so it can interact with other applications present on the victim’s mobile device. Using the app’s permissions, the malware controller can access the device’s screen, keeping a real-time surveillance tactic that enhances the information theft capabilities of the controller.

The real-time surveillance feature allows the trojan to turn off the device’s screen in order to perform actions without the user’s knowledge. So far the main use for BRata is the theft of banking credential login information, and two-factor authentication tokens. However, due to the trojan's vast capacities, it may likely evolve into another type of malicious variant, used for extortion-related threats or even ransomware attacks.

The Latin American region is the first potential target of BRata: 81% of the region uses Android; against only 17% of iOS users. However, so far BRata infection has not been identified in any other country. Yet, BRata is being sold in WhatsApp and Telegram groups for R$3,000 (around $560).

Mitigation Note

The main infection vector of BRata has been the download of WhatsApp fake updates. Yet to update any app, it is not necessary to download a new version; instead, the legitimate app will warn the user about updates available and then proceed.

It is crucial to review the app’s requested permissions. If the app requests permission to access too many functionalities that are not related to its operational necessity, the user shall be cautious and question the legitimacy of such an app. Having any anti-virus solution is also a good key to keep a mobile device safe from malware variants that will harm the user’s privacy.

Tetrade: The Internationalization of Brazilian Banking Trojan Families

A new trend in the global cyber scene is the Tetrade: four Brazilian banking malware variants that were previously only employed nationally, but that are currently being employed in attacks in other Latin American countries, and even in European ones. The four banking trojan families are Guildma, Javali, Melcoz, and Grandoreiro.

Brazilian banking trojans were timidly being employed only in Brazil up to 2011, but from that year on, they have been employed in other Latin American countries, and also in Europe. There is a forecast that soon enough they will be also employed in the US and China. Since late 2019, 3,500 Tetrade attacks have been registered worldwide: targets were located in Brazil, Chile, Mexico, Portugal, and Spain. After going international, Brazilian cybercriminals have started recruiting international partners: the server’s owners provide access to a botnet that sells the software to international criminals - so they can also perpetrate attacks and have access to the stolen money. Consequently, not only the attacks are profitable, but Brazilian hackers have also been adopting the idea of MaaS (malware-as-a-service).

Among the four trojans identified in the Tetrade, Guildma (also known as Astaroth) is the oldest running malware family. It has been active at least from 2015 on, and it uses phishing emails with the malware in compressed format as infection vectors. After infection, Guildma connects to a YouTube channel or a Facebook page where it retrieves an encrypted text with the link to the command-and-control server, so the trojan can receive directives and to where it can send stolen data for storage. As a banking trojan, Guildma can perform very specific functions related to online banking operations: through Virtual Network Computing (a desktop-sharing system), it gains full webpage navigation control; it can request SMS tokens, QR code validation, and other transactions.

The second trojan family is Javali, active since November 2017, which targets bank customers from Portuguese and Spanish-speaking countries. However, it also targets cryptocurrency websites (Bittrex, for example), and payment tools (Mercado Pago, for example). It operates similarly to Guildma, resorting to phishing emails to infect machines; and it also uses YouTube to host the communication between the malware variant and the command-and-control server.

Melcoz is active internationally since at least 2018 and has been targeting Spanish-speaking countries such as Mexico, Chile, and Spain. Since Brazilian coders speak a different language, this international expansion has likely been made possible by a partnership with local groups of coders and mules to deal with stolen money. Melcoz is a variant of a RAT (Remote Access Trojan), and it also spreads via phishing emails. The trojan monitors browser activities (be it Mozilla Firefox, Google Chrome, or others) to spot online banking sessions. Once the code finds it, it displays an overlay window in front of the user’s browser to manipulate the banking information in the background.

Finally, Grandoreiro trojan is active since at least 2016, and from 2019 on it has started being employed abroad - especially in Mexico and Spain. It spreads through spam: usually using fake pop-ups to get their victims to insert personal credentials; but lately, phishing emails Covid-19-related are also a tool for the spread of the malware. Once the Trojan infects the device, its backdoor manipulates the victim’s browser, records keystrokes, and may even block access to certain websites. Finally, Grandoreiro has also been employed as a MaaS.

Mitigation Note

The four trojan families that constitute Tetrade usually rely on email phishing campaigns to infect machines. As such, the first recommendation is to be always cautious with unknown incoming emails. Checking the authenticity of this email is an important step to mitigate malicious emails. If the receiver does not recognize the authenticity of the email, it is essential not to open any attached files, which may contain any sort of malware variant.

The use of multi-factor authentication methods increases the safety of the user through the use of different security layers. Resorting to password management tools is also good mitigation to the keylogging issue since it allows the user not to physically type passwords.

Finally, regularly running security scans on the user’s machine is also a vital step to mitigate the infection; if prevention fails, the user can still rely on quick incident response capabilities.

Cybercrimes Targeting Financial Institutions

Globally, the financial sector is the second most affected sector by cybercrime - behind only retail. This reality is not different in LATAM. Banks and other financial institutions face challenges that regard fraud, be it due to identity theft (as discussed above) or trojan and backdoor mechanisms. The Emotet botnet (targeting mostly banks) presence in the region represents 45% of the global employment of the tool. In general, in 2019, LATAM suffered 85 billion attack attempts in regards to malware variants and botnet activity, the most affected country is Brazil with 24 billion cyberattacks in a year.

Below some fraud schemes are discussed to illustrate the inventiveness employed by Latin American cybercriminals when targeting banks and other financial institutions. The lesson drawn from these examples is that such institutions must keep track of intelligence data in order to stay one step ahead of the cybercriminal world, otherwise, the financial losses related to fraud schemes do not seem to be decreasing anytime soon.

Case studies

BINero Fraud

The BINero fraud is a strong trend in Spanish-speaking countries, especially Mexico, and it was first detected in 2015. Due to the strong Binero community in social media (not only in Dark Web forums), there are numerous tutorials available online, which allows more and more people to commit this kind of fraud - many of which are minors.

The BINero fraud consists of finding a fraudulent BIN (bank identification number) in order to proceed with online payments. Every card has at least 16 digits, and the initial 4 to 6 digits correspond to the BIN, which identifies the issuing bank and the type of card. The BINero fraud, then, aims to discover BINs that get improperly validated by online payment processors. Through manual trial and error, the criminals try to identify websites where there is a disbalance between the bank behind the BIN and the online retailer type of card validation. These vulnerabilities are explored by cybercriminals: once this combination of website and fraudulent BIN is discovered, fraudsters use special programs that can generate the remaining information (the remaining card’s digits, CVV, expiration date) to complete the transaction.

These fraudsters avoid using real cards; instead, they exploit system vulnerabilities to target banks and companies, not banking users. Using authentic cards is also a possibility for this community, but it is not their main tactic. As a result, in Mexico, for example, the BINero fraud produces financial losses that mount up to 12,500 million Mexican pesos (around $675 million) per year. These losses are shared between banks and retailers, and it hardly affects users. The Spanish-speaking community of BINero fraudsters has a specific vocabulary: if it is the case to use authentic cards, for example, they call it quemar (to burn); and they usually do not steal large amounts of money, instead, they call their small thefts hormiga (ant).

The BINero fraudsters mostly use this tactic to purchase immediate delivery services, mainly entertainment-related, such as streaming services - Netflix, Amazon Prime, Spotify, etc.

Mitigation Note

If it is the case that one of the combinations generated by the special software results in the use of an authentic card, this means that a user was a victim of fraud. To avoid that, some recommendations might improve the safety of users. The first one is to constantly check the account balance and transactions to try to spot any unidentified movement as soon as possible - and communicate this incident to the bank. The user can also activate mobile phone notifications to keep track of the use of their personal card in real-time.

Some banks offer alternative cards, related to the user’s main account, exclusively for Internet use - and they also block the physical card for online transactions. This type of online card minimizes the possibility of fraud since the banking app constantly shifts the CVV - which diminishes the risk of fraud and improves the user’s safety.

Ploutus, the First Latin American Jackpotting Malware Variant

Jackpotting malware variants are specifically designed for automated teller machines (ATMs). The objective is to make the machine release money on the command of the malware variant activation. After the infection, there are two modalities of attack: remote and in person. The first one provides more safety to the cybercriminal, who activates the malware variant from a distance, and a money mule collects the money. One of the first campaigns of the genre is known as Ploutus, a common jackpotting attack that spread from Mexico to the rest of Latin America.

Targeting the banks, not their users, jackpotting attacks are a nightmare to Latin American financial institutions. Since its launch, in 2013, Ploutus has produced a financial loss that mounts up to $450 million. Its first malware version was delivered through CD-rooms, but it has evolved a few times so it could be delivered through USB tethering. Ploutus has been considered the most sophisticated variant of ATM malware, especially because it could be activated through SMS messages, with no need for a credit/debit card. Ploutus malware is capable of withdrawing 400 money bills from each of the available denominations for around 3 hours.

Ploutus has evolved from its initial malicious coding. The latest version identified, Ploutus-D, also known in the Spanish-speaking hacker scene as Piolin (Tweety, the yellow canary cartoon), is being employed not only in Mexico but also in other American countries. Piolin interacts with multi-vendor ATM Software Kalignite (KAL), a platform that runs in over 80 countries, which includes, among others, the US, Chile, Colombia, Peru: the cyber-threat is getting international.

Due to coding components written in Spanish, and also due to the area of attacks, Ploutus and its later variants are believed to have originated in a Latin American country. It is most likely that the jackpotting malware variant is indeed Mexican, or, as some have suggested, a partnership between Mexican and Venezuelan hackers. These cybercriminals did not exploit a system vulnerability to develop their malicious code; instead, they have had access to the software code of the infected machines - be it through physical theft of an ATM machine or a partnership with a software developer employee.

Mitigation

Since there has to be a physical component for the machine compromise, an infection can be stopped through the use of hardware protection tools - blocking the use of USB or keyboard external devices. Using full disk encryption is also an important step to avoid software manipulation by external systems.

Even in the case that infection could not be avoided, employing further protection tools might mitigate the issue of jackpotting malware variants. Employing an application whitelisting might protect the system of running the launcher and the malware itself in the ATM machine.

Conclusion

The hacker community in Latin America grows in parallel to the spread of the Internet in the region. The integration of such communities in the digital domain creates the environment for the flourishing of e-commerce: the region is the second-fastest-growing e-commerce market in the world. Last year, retail e-commerce sales mounted up to $70 billion, and by the end of 2020, the projections are that the market will grow up to $83,6 billion. Furthermore, concomitantly to the Internet penetration in LATAM, the region experienced a regional economic growth that provoked a financial inclusion trend in the region. Financial inclusion translates into the following statistics: in 2011, only 39,4% of the Latin American population had bank accounts; in 2017, this percentage grew to 55,1%.

New hacker groups increasingly flourish in Latin America, creating their own communities of Spanish/Portuguese-speaking cybercriminals. Within these groups, banking trojans families are fairly common across the region. These malware variants are usually looking for private financial information from internet banking users. With the rising popularity of cryptocurrencies, banking trojan families are no longer targeting only formal banking institutions and their users. The design of banking trojan variants increasingly includes functions related to cryptocurrency wallets. In Latin America, where these currencies are progressively popular, fraud schemes that encompass cryptocurrencies are a trend. Due to the untraceable feature of these currencies, digital currencies are useful tools for money-laundering, drug dealing, and any sort of frauding scheme.

Such developments will likely be a major trend for the region's economic & digital security in the coming years.

Advanced Intelligence is an elite threat prevention firm. We provide our customers with tailored support and access to the proprietary industry-leading “Andariel” Platform to achieve unmatched visibility into botnet breaches, underground and dark web economy, and mitigate any existing or emerging threats.

Beatriz Pimenta Klein was leading the Latin America cybercrime research project at AdvIntel through the year 2020. She graduated from the Federal University of Santa Catarina, Brazil, with a Bachelor's Degree in International Relations. Beatriz is currently a Master's student in International Security Studies at the University of Trento/Scuola Superiore Sant'Anna, Italy. This series presents the findings for Ms. Pimenta Klein's findings developed through the year 2020, during the author's time in AdvIntel. The author declares that there is no conflict of interest with her current work position.